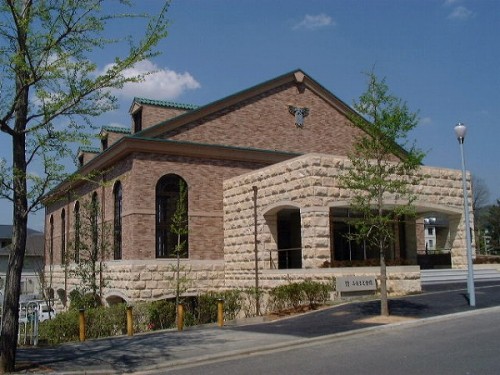

Dr. Barbara Ambros, associate professor at the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill, was invited to give a presentation at Tenri University Furusato Assembly Hall on July 11. An invitation was extended to Dr. Ambros to speak in Tenri after she had written an article on CNN’s Belief Blog about how Japan’s new religions responded to the March 11 earthquake and tsunami that briefly showcased Tenrikyo and the efforts of the Disaster Relief Hinokishin Corps.

Dr. Ambros’ presentation, which she gave in Japanese, was entitled “Nakayama Miki’s Views on Women and Their Bodies: In the Context of Late Edo and Early Meiji Period Religion.” She noted how several academic treatments of Tenrikyo’s founder have tended to cast Miki as a proto-feminist figure who sought to liberate women from the constraints of a patriarchal society.

While Miki may have freed women from conforming to prevailing pregnancy taboos and rejected the widespread belief that menstrual blood was impure, Miki nevertheless reinforced the traditional ideal for a wife to be submissive to her husband as a means to achieve domestic harmony. Dr. Ambros argued that it was necessary to view Miki’s efforts to free women from popular superstitions surrounding pregnancy in the context of the soteriological worldview she propagated since she was equally focused on bringing salvation to men in addition to women.

Dr. Ambros then described two other popular religious movements that predated Tenrikyo’s emergence to serve as points of contrast and comparison: Nyoraikyo and Fujido.

First, Nyoraikyo may be notable in that it was also founded by a peasant woman named Kino (later known as Isson Nyorai Kino; 1756–1826) in modern-day Aichi Prefecture. However, contrary to one’s expectations, Nyoraikyo tended to reinforce prevailing misogynistic religious views. A major discourse in the Nyoraikyo canon argued that because Kino was a woman, this proved that her message came from a divine source since a woman could not be seriously be considered as a progenitor of such religious knowledge in feudal Japan. (Interestingly, this line of argument is similar to what can be read in a Divine Direction from January 8, 1888.)

Fujido was a religious movement centered on the worship of the deity of Mt. Fuji (Sengen Daibosatsu) that was founded by Kakugyo Tobutsu (1541–1646) and later popularized by Jikigyo Miroku (1671–1733). In addition to propagating belief in a parental deity, just as Miki deliberately inverted “heaven and earth” (tenchi) into “earth and heaven” (ji to ten) in The Songs for the Service, Fujido also deployed similar word order inversions, reflecting the idea that the relationship between the sexes had to be realigned to establish a harmonious social order.

References

Kanda Hideo. “Religious Thought of Nyoraikyō.” Tenri Journal of Religion 22 (December 1988), pp. 59–89.

Sawada, Janine Tasca. “Sexual Relations as Religious Practice in the Late Tokugawa Period: Fujidō.” Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 32:2 (Summer 2006).

Tyler, Royall. “The Tokugawa Peace and Popular Religion: Suzuku Shōsan, Kakugyō Tōbutsu, and Jikigyō Miroku.” In Confucianism and Tokugawa Culture (Peter Nosco, ed.), pp. 92–119.

Further reading

- CNN Mentions Tenrikyo’s Disaster Relief Efforts [TR]

- CNN Blog Highlights Tenrikyo’s Postquake Relief Activities [Tenrikyo Online]

- My Take: Japanese new religions’ big role in disaster response [CNN]

Image source: http://www.furusatokai.gr.jp/kaikan/index.html